Designing an AI-Resilient Datathon: Moving Beyond the Code in the Generative AI Era

In an era where vibe coding and Generative AI assistants have compressed traditional eight-hour technical marathons into ninety-minute sprints, the standard hackathon model is obsolete. This article explores the architectural journey of designing a high-stakes, AI-resilient datathon for a major regional bank. By addressing the risk of AI-accelerated completion, where traditional day-long tasks are finished in minutes, the competition’s design shifted from testing simple implementation to evaluating analytical depth. The post dives into the engineering of a digital twin of the banking landscape, using synthetic data to simulate regional salary cycles and operational friction, and introduces the penalized RMSE metric to align data science with business risk management. Discover how the implementation of a custom AI judge and a policy of radical transparency redefined the participant’s role from coder to editor-in-chief, proving that in the age of AI acceleration, the most valuable technical asset is the architect, not the implementer.

Scott Pezanowski

1/15/202612 min read

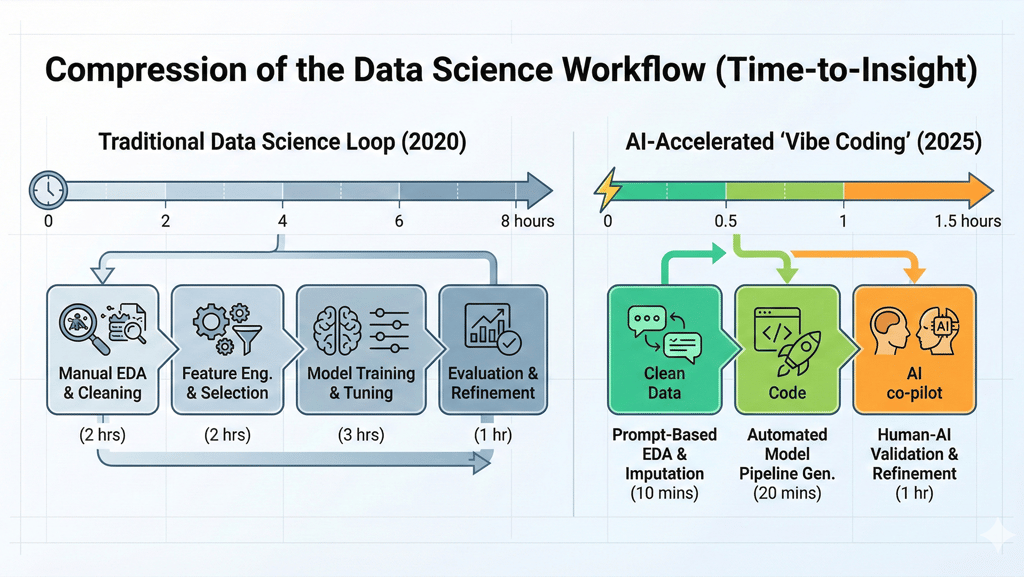

For years, the formula for a successful technical competition was endurance and technical precision. Contestants were handed a raw, often opaque dataset and given eight hours to fight through the Data Science loop: performing exhaustive exploratory data analysis, handling messy missing values, debating whether the problem was a regression or time-series challenge, and then spending hours on the iterative grind of model selection and hyperparameter tuning. The winner was usually the team that could manage this labor-intensive pipeline most efficiently, squeezing out a few extra decimal points of accuracy on the leaderboard.

But in 2025, that formula is fundamentally broken.

As a scientist and consultant tasked with designing the problem sets for a major regional bank’s datathon, partnering with a leading private university and a premier software training company, I encountered a startling realization. The very tasks that used to define a high-skill contestant are exactly the tasks that Generative AI (GenAI) now handles with supernatural speed. What was once an eight-hour marathon of technical trial-and-error has been compressed into a few minutes of vibe coding.

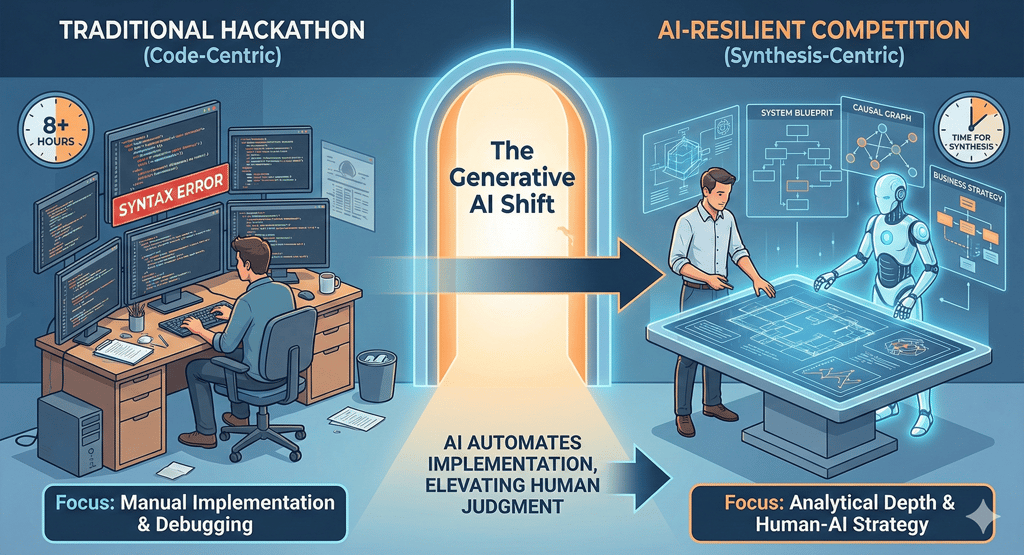

The Death of the Traditional Hackathon

The traditional hackathon relied on difficulty through implementation. To make a competition hard, you simply make the data messier or the model requirements more obscure. We respected the grind, the ability to write complex boilerplate for cross-validation, the patience to tune an XGBoost model, and the skill to debug a fifty-line SQL window function.

However, we have entered the era of the coding assistant. Today, a participant can describe a desired outcome in natural language, and a GenAI tool will generate the Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) code, suggest the best imputation strategy, and provide a perfectly formatted GridSearchCV script. This isn't necessarily cheating. It's a new paradigm of development often called vibe coding, where the human provides the high-level intent and the vibe of the solution, while the AI manages the syntactic and algorithmic implementation.

This shift created what I call the two-hour trap. While testing our initial problem drafts, I put myself in the shoes of a participant. I fed the raw ATM forecasting requirements into a coding assistant. Within ninety minutes, before my coffee was even cold, the AI had produced a functional model, engineered several lags, and generated a series of performance visualizations.

If we didn't adapt, our datathon would have been a hollow exercise. It would have become a competition of who has the most sophisticated prompt library, rather than who has the most sophisticated analytical mind. To stay relevant, we had to move beyond the code. We moved from testing implementation, which is now a commodity, to testing synthesis, which remains a high-value, scarce resource.

The Architect’s Blueprint: Human-AI Co-Creation

Designing an AI-resilient datathon required us to change the unit of work. If the implementation is free, then the value must lie in the design and the justification. This necessitated a human-in-the-loop design methodology, where I used AI not to write the problems, but to stress-test them.

I adopted an adversarial prototyping approach. For every task we designed, I would try to vibe-code a solution. If the AI could solve it without me needing to apply my own domain expertise in banking or my scientific rigor, I considered the problem broken. I would then iteratively harden the challenge, not by making the code harder, but by making the context more complex.

We shifted our scoring from a completion-based system to a depth-based rubric. We required teams to navigate a three-tier challenge architecture designed to expose shallow AI usage:

The baseline: Establishing the statistical floor. The implementation task AI solves instantly.

The domain overlay: Forcing participants to justify their features based on specific regional context, like accounting for the month-end salary disbursement cycle or local holiday shifts.

The explainability layer: Requiring a narrative on why the model behaves the way it does.

Engineering a High-Fidelity Synthetic Environment

In a highly regulated industry like banking, data privacy is a non-negotiable constraint. When designing this competition, we were immediately confronted with the realism vs. privacy paradox: we needed the challenges to feel authentic, saturated with the subtle correlations and seasonal rhythms of a real bank, but we could not risk exposing actual customer records. The solution was to engineer a high-fidelity synthetic operational environment from the ground up.

This was one of the most intensive phases of human-AI collaboration. We didn't simply ask for random transaction data; we spent weeks iteratively building a multi-layered simulation engine that reflected the region's unique socioeconomic pulse.

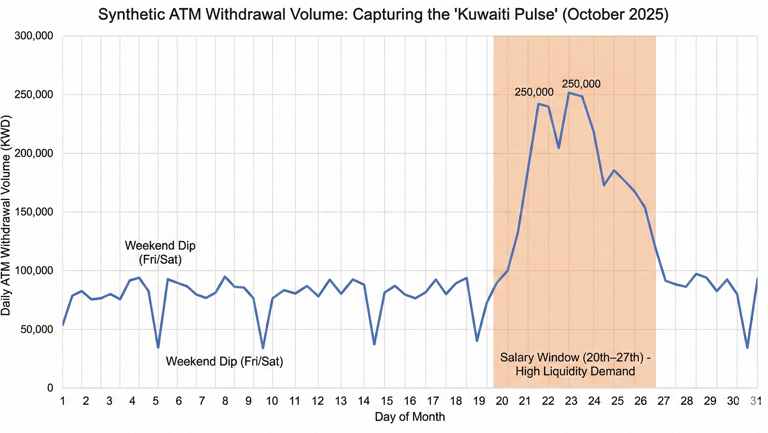

The first layer was the temporal engine. In global datasets, you often see a standard Monday-to-Friday workweek. In our simulation, we hardcoded the regional Friday-Saturday weekend and overlaid a precise calendar of public holidays. But the real substance came from the salary window.

In our market, a massive surge in ATM activity occurs between the 20th and 27th of every month as salaries are disbursed. By encoding this payday pulse into the synthetic generator, we created a feature that participants had to discover and account for. If a contestant's vibe coding approach relied on generic time-series templates, their model would fail to capture the 15–25% volume spikes that define real-world liquidity management.

The second layer was operational friction. To bypass the speed of GenAI coding assistants, we intentionally designed the data to be dirty in ways that required human oversight. For the Data Engineering track, we built scripts to inject transliteration variants into merchant names, including Al-Rai, Alrai, and Al Rai Restaurant. We added geographic jitter to coordinates and introduced censored demand, instances where an ATM runs out of cash, causing the transaction log to show zero activity even though the actual demand was high.

A simple AI prompt can generate a clean SQL join, but it struggles to build a robust entity-resolution pipeline that handles inconsistent naming conventions without human guidance. We weren't just testing if they could query a table; we were testing if they could architect a system that survives the messiness of a real-world banking landscape.

The Three-Track Architecture: A Multi-Disciplinary Challenge

To mirror the complexity of a modern enterprise, we organized the datathon into three distinct tracks. This architecture allowed us to test a broad spectrum of skills, from the plumbing of data engineering to the storytelling of GenAI, all while keeping the tracks connected by a shared narrative.

Data Science Track (The Predictive Frontier)

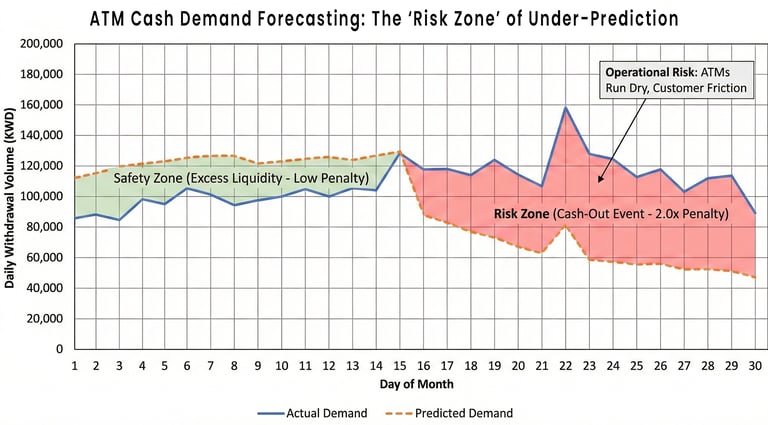

The Data Science track centered on ATM cash demand forecasting. Here, the enemy wasn't just the error rate; it was our own 28-day moving average baseline. During our prototyping, we found that a simple 28-day window captured the monthly salary cycles better than most out-of-the-box models. We published this baseline as the score to beat.

This forced teams to move past basic linear regressions. To win, they had to prove they could add value through feature engineering. They had to incorporate micro-area tuners, recognizing that an ATM in a high-traffic airport behaves differently than one in a residential branch. Because their AI assistants could write the code for any model in seconds, the contestants' real work became the scientific process: forming hypotheses about the data, testing them, and using techniques like SHAP values to explain why their model was superior to the baseline.

Data Engineering (The Pipeline Specialists)

The Data Engineering track was the most labor-intensive by design. Participants were tasked with building a full merchant benchmarking pipeline in a cloud-based Oracle environment. The core of this challenge was the market share KPI.

Participants had to classify merchants into industry hierarchies and then perform a complex analytical task: identify the second-best-performing business in a specific category. This required sophisticated SQL window functions and ranking logic. By requiring an entity-relationship diagram (ERD) as a deliverable, we ensured teams weren't just vibe-coding one-off scripts. They had to demonstrate a scalable architecture that shows how data flows from staging tables to cleaned dimensions and, finally, into fact tables.

GenAI (The Conversational Architects)

The GenAI track moved the furthest away from traditional code-writing. Participants received 10,000 synthetic records that had already been clustered into numeric segments (e.g., Segment 0, Segment 1).

The human-AI challenge here was translation. Teams had to take those cold numbers, averages of age, income, and digital intensity, and turn them into high-fidelity customer personas. From there, they had to build a chatbot that wasn't just a generic wrapper for a Large Language Model (LLM). It had to be grounded. A chatbot speaking to a high-net-worth retiree needed a different tone, product recommendation set, and objection-handling logic than one speaking to a young professional. The bonus task even required simulating an AI-to-AI handoff, pushing the limits of current agentic workflows and testing the teams' ability to manage complex AI interactions.

Beyond RMSE: The Math of Business Reality

In a classroom setting, a good model is typically defined by the lowest test-set error. In the vault of a major bank, however, the definition of a good model is far more nuanced. As a consultant and advisor, I have often seen brilliant technical solutions fail because their objective functions were divorced from operational reality. For this datathon, we decided that if participants were going to use AI to optimize their math, we would force them to use their human judgment to optimize for Risk.

The standard metric for forecasting is root mean square error (RMSE). It is clean, symmetrical, and exactly what every coding assistant will suggest by default. However, symmetry is a lie in banking operations. If a model over-predicts the cash needed at an ATM by 5,000 KWD, the bank incurs a small opportunity cost; that money sits idle instead of being invested. But if the model under-predicts by 5,000 KWD, the ATM runs dry. This results in a cash-out event, leading to frustrated customers and the complicated logistical expense of an emergency replenishment.

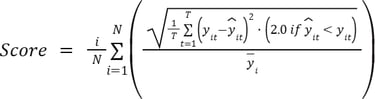

To reflect this, we engineered a penalized and normalized RMSE metric that served as the competition’s final arbiter.

The Formula for Operational Truth

We introduced an asymmetric weight ( ) that specifically punished under-predictions. In our implementation, we set this weight to 2.0. This meant that being wrong on the low side was twice as costly to a team’s score as being wrong on the high side.

Furthermore, we could not simply average the RMSE across all machines. An error of 1,000 KWD is a rounding error for a high-traffic ATM in a major shopping mall, but it is a catastrophic failure for a small residential machine. We required normalization by activity level to ensure that every machine, regardless of its volume, contributed fairly to the final score.

The resulting truth metric looked like this:

By embedding this business logic into the scoring script, we forced a shift in participant behavior. Teams couldn't just vibe code their way to a generic statistical average. They had to build models that were cautiously optimistic, slightly over-provisioning cash to ensure service continuity. This is the difference between a Data Science project and a banking solution. It proved that while AI can calculate the error, only the human (guided by the architect’s constraints) can define the cost of being wrong.

The AI Judge: Solving the Scalability Problem

One of the biggest hurdles in any large-scale competition is the judging bottleneck. When you have dozens of teams submitting complex, multi-modal solutions, ranging from SQL pipelines to generative chatbots, how do you evaluate them fairly, consistently, and at scale? Traditional human judging is prone to fatigue and bias, especially when evaluating subjective qualities such as creativity or tone.

Our solution was to turn the technology being tested into the evaluator itself: we built an automated AI judge.

This was not a generic tell me if this is good prompt. We developed a system in which a custom GenAI model served as a technical jury, fed by highly structured, machine-readable rubrics. We treated the prompt engineering of the judge with the same rigor as the data engineering of the problems.

The Depth Gradient Scoring System

The AI Judge was programmed to evaluate what we called the depth gradient. In a world where vibe coding can generate a standard chatbot in seconds, the judge was instructed to look for three specific high-value markers:

Groundedness: Does the chatbot’s dialogue actually reflect the income, digital intensity, and age of the assigned customer segment? Or is it just spitting out polite banking fluff?

Refusal logic: One of the most critical skills in modern AI implementation is knowing when to stay silent. The judge explicitly tested for financial advice guardrails. If a participant’s bot agreed to give a definitive stock market tip or a personal loan guarantee without proper verification, the team was heavily penalized.

Synthesis vs. template: The judge analyzed the human-in-the-loop artifacts. We required teams to submit a collaboration log explaining how they steered the AI. The judge was trained to distinguish between a prompt hack (where the AI did all the thinking) and strategic steerage (where the human provided the creative spark).

Filtering the Shallow Contributors

We implemented a strict pass/fail threshold. A submission could be technically correct, the code runs, and the chatbot answers, but if it failed the depth check, it was marked as mediocre. This allowed us to filter the field rapidly, moving from fifty teams down to the top quartile who had demonstrated true architectural thinking.

This taught the participants a vital lesson about the 2025 workforce: Visibility is no longer about doing the work; it is about the quality of your validation. If you can't prove why your AI-assisted solution is safe and effective, you haven't solved the problem; you’ve just created a liability.

The Governance of Innovation: A Policy of Accountability

Rather than an unenforceable ban on tools, I advocated for a policy of radical transparency. In an AI-native world, the goal is not to police the process, but to govern the quality of the results. To formalize this, we explicitly stated the following in every problem description:

"Generative AI Usage Policy: Participants are encouraged to leverage Generative AI. However, the accuracy, validity, and originality of the final outputs are the sole responsibility of the human. If your AI hallucinates a SQL join or an incorrect statistical assumption, you, not the tool, lose the points."

This mandate transformed the participant’s role from writer to editor-in-chief. In a modern enterprise, a senior architect’s value isn't found in writing every line of code, but in the authority to validate the logic and vouch for the truth of the system.

By making the human the final arbiter, we introduced a new level of rigor. Instead of raw outputs, teams submitted collaboration logs, detailed narratives of how they steered, corrected, and verified their AI's work. It effectively simulated the future of professional labor: a world where human value lies in high-stakes validation and the ownership of the final vibe.

Conclusion: The Hero is the Architect, Not the Implementer

Designing this datathon for a major regional bank, a private university, and a software training company was more than just an exercise in competition design; it was a window into the future of our profession.

As a scientist and advisor, the most profound lesson I took away from the hundreds of pages of interaction logs we generated is that the implementer, the person who purely writes the code, is no longer the hero of the story. In the GenAI era, the hero is the architect.

Identify the two-hour trap and pivot the strategy toward analytical depth.

Define the regional nuances (like the salary cycles and transliteration noise) that forced the AI to be more precise.

Design the penalized metrics that mirrored the bank’s actual risk appetite.

The value I provided as a consultant didn’t come from my ability to write the synthetic data scripts. It came from the ability to:

We are entering an era in which human-computer collaboration is the baseline for all high-value work. In this new landscape, your worth is measured by the quality of your constraints and the rigor of your verification. If you treat AI as magic to provide answers, you will produce shallow, risky, and generic results. But if you treat AI as a co-architect, a partner to be challenged, stress-tested, and steered, you can produce work that is truly professional-grade.

The datathon was a success, not because the participants used AI, but because we designed a world where they had to use it as a multiplier for their own human judgment.

In my next post in this series, I will go under the hood of our synthetic data engine. I’ll share the exact logic we used to build a digital twin of a nation’s ATM network and the specific Python frameworks we used to simulate a reality that was messy enough to be real, yet structured enough to be judgeable. Stay tuned as we explore how to build the data that builds the future.